The SLAB Memory Allocator

One of the primary things an operating system does is allocate memory. In this tutorial we’re going to write our very own memory allocator for the rest of the kernel to use to allocate memory. This will allow us to more safely use and allocate strings and implement more complicated data structures which will come in useful later!

In this tutorial I’m going to focus on the SLAB Memory Allocator used in the Linux operating system which eliminates memory fragmentation caused by allocations and deallocations. In an operating system this is usually built on top of the Virtual Memory system which maps 4KB blocks of memory. This means the goal of the allocator is to chop those 4KB blocks up into more manageable pieces.

The virtual memory system provides an API where you can map a 4K block of memory to a specific memory address. In my kernel it looks like this:

void map_page(u32 virtualAddr);

If you fail to call map_page and attempt to read/write from a memory location that isn’t mapped then you get a page fault. I plan to talk in more detail about the virtual memory system in a future tutorial.

Allocator API

First off let’s define the interface to our memory allocator. We don’t want to confuse it with malloc so I’ve gone with kalloc. I also like to avoid sprinkling unsigned everywhere so let’s add some typedefs.

typedef unsigned int u32;

typedef unsigned short u16;

void kalloc_init(u32 memStart, u32 memSize);

void* kalloc(u32 size);

void kfree(void* ptr);

kalloc_init allocates a range of memory and sets everything up. We would call this from our kernel setup routine after we’ve initialised the virtual memory system.

Slab Algorithm

The core idea of the SLAB allocator is that you split each 4K block (from now on a Slab) into an array of blocks of the same size. For example a 4K slab can hold exactly 4 x 1024 byte objects and 32 x 128 byte objects. To avoid wasting space the object size must be a power of 2.

When you request a block of memory of a specific size the allocator finds a slab with objects that are the next power of 2 of that size and hands you a free block from it. If there are no free blocks left then a new slab is mapped from virtual memory.

Free memory inside a slab is tracked via a linked list where the pointer to the next free element is stored inside the free memory location itself! This constrains us to a minimum allocation size of 32 bits so we can store the pointer.

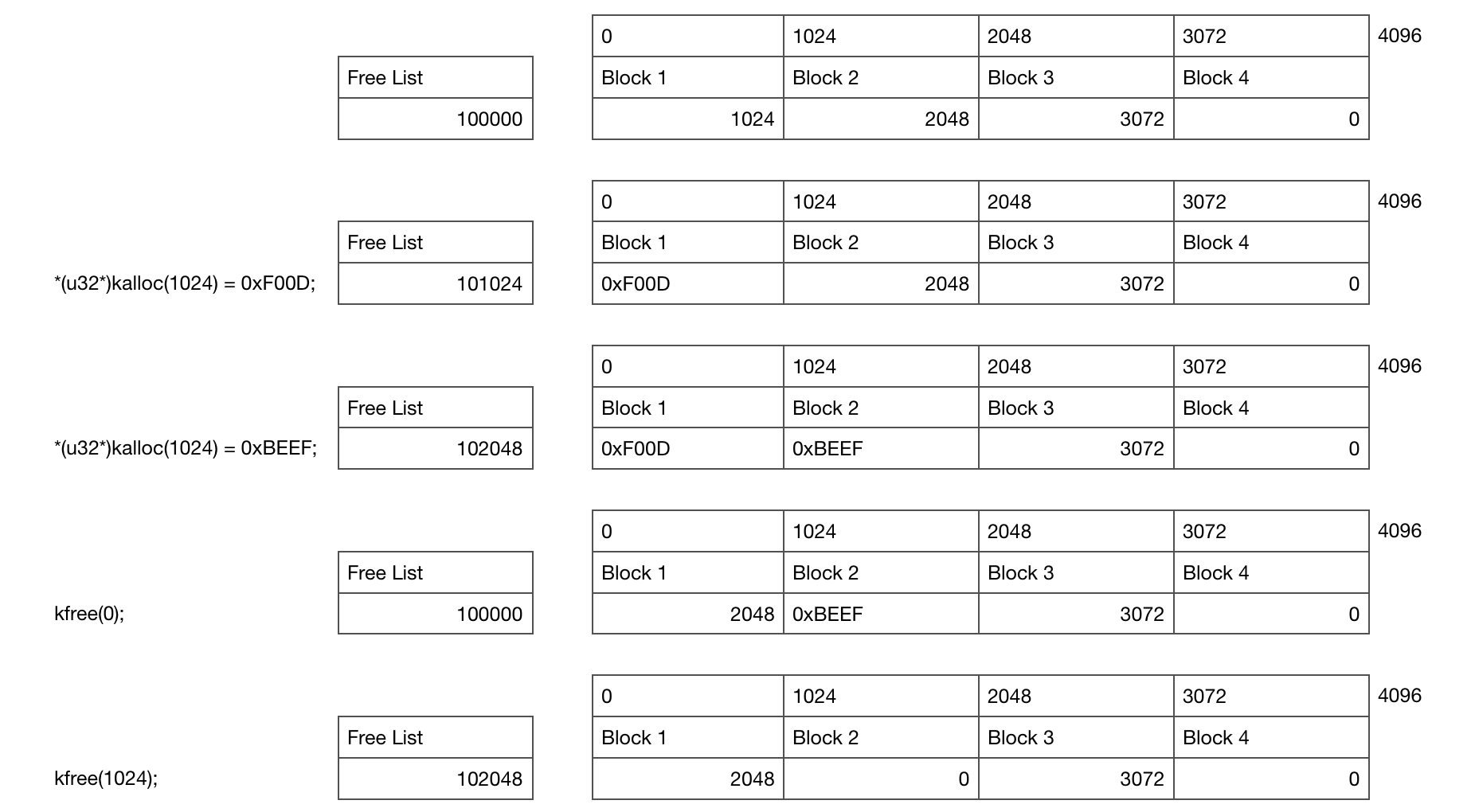

Allocation within a Slab

This diagram shows what’s going on for a single Slab as you allocate and free memory. In this example you start with a single 4KB Slab containing 4 x 1KB objects which has been allocated at location 10000 in memory. An unaligned low memory location like this is a bad idea in the real world but this makes it easier to understand ;)

Initially the free list is pointing at the first block, which is pointing to the second block and so on until we hit the null pointer at the end.

The first kalloc allocates 1KB of memory and writes 0xF00D to it which updates the free list pointer to point at the second block of memory. The second writes 0xBEEF and points the free list at the third block.

When the memory is freed we simply write the free list location into the freed memory location and update the free list to point at our freed block.

Let’s go ahead and write some code for this!

struct SlabEntry

{

SlabEntry* next;

};

struct Slab

{

Slab* m_nextSlab;

SlabEntry* m_freeList;

u32 m_slabStart;

u16 m_size;

void Init(u32 slabStart, u16 size);

bool Alloc(u32 size, u32& newLoc);

bool Free(u32 location);

};

First we need to initialise the memory for a single slab by setting up the free list to point to each block of free memory. Initially this will be every block of memory in the slab, like this:

void Slab::Init(u32 slabStart, u16 size)

{

m_nextSlab = nullptr;

m_slabStart = slabStart;

m_size = size;

map_page(slabStart);

memset((void*)slabStart, 0, 0x1000);

u32 numEntries = (0x1000 / size) - 1;

m_freelist = (SlabEntry*)slabStart;

SlabEntry* current = m_freelist;

for (u32 i = 1; i<numEntries; i++)

{

current->next = (SlabEntry*)(slabStart + (i * size));

current = current->next;

}

}

This function takes a virtual memory location which we will ask to be managed by this slab and the size of each object we’ll be allocating. We ask the virtual memory paging system to map this page for us and make it writeable.

Next the alloc function pops a free object off the free list!

bool Slab::Alloc(u32 size, u32& newLoc)

{

if (m_size != size || m_freelist == nullptr)

return false;

newLoc = (u32)m_freelist;

m_freelist = m_freelist->next;

return true;

}

The free function adds an object back on the free list, after checking that the memory location being freed is within the slab:

bool Slab::Free(u32 location)

{

if (location < m_slabStart || location >= m_slabStart + 0x1000)

return false;

SlabEntry* newEntry = (SlabEntry*)location;

newEntry->next = m_freelist;

m_freelist = newEntry;

return true;

}

There is a whole bunch of extra checks you can do here which I’ve left out to make the code simpler.

Allocating Slab Metadata

So at this point we have a way of allocating memory for a single 4KB block of memory for a single allocation size. How do we build on this?

We want to support multiple slabs of memory! The simplest option is to have a linked list of them, like this:

Slab* g_slabList;

This brings up another problem. Where do we store the members inside each Slab struct? The answer is to store the Slab structs inside a special list of Slabs set aside just for this purpose - a ‘metadata’ slab.

Slab* g_slabMetaData;

Here is helper function alloc_slab_meta that will set one of these up. The trick here is to use the first object in the slab to store the fields of the metadata slab itself. It’s turtles all the way down!

static Slab* alloc_slab_meta(u32 slabStart)

{

Slab slabMetadata;

slabMetadata.Init(slabStart, sizeof(Slab), true);

u32 slabLoc;

bool didAlloc = slabMetadata.Alloc(sizeof(Slab), slabLoc);

assert(didAlloc && slabStart == slabLoc);

Slab* newSlabMeta = (Slab*)slabLoc;

*newSlabMeta = slabMetadata;

return newSlabMeta;

}

Putting it all together

We need to know where our heap needs to start from in virtual memory:

u32 g_memStart;

We’re ready to write our kalloc function! First we loop through the existing slab lists to see if we can allocate memory from those:

void* kalloc(u32 size)

{

u32 newLoc;

Slab* slab = g_slabList;

for (; slab; slab = slab->m_nextSlab) {

if (slab->Alloc(size, newLoc)) {

return (void*)newLoc;

}

}

If that fails then we need to allocate a new slab, and hand over the first block of memory from there. The memory for slabs is held by the g_slabMetaData which we can now allocate from:

u32 slabLoc;

bool didAlloc = g_slabMetaData->Alloc(sizeof(Slab), slabLoc);

If the metadata is full then we need to allocate a new metadata slab! Since this allocator never throws away allocated slabs we don’t need to keep a reference to previous metadata slabs.

if (!didAlloc) {

g_slabMetaData = alloc_slab_meta(g_memStart);

g_memStart += 0x1000;

g_slabMetaData->Alloc(sizeof(Slab), slabLoc);

}

Now we have somewhere to put the metadata we can allocate a new slab and add it to the slab list!

Slab* newSlab = (Slab*)slabLoc;

newSlab->Init(g_memStart, size, false);

g_memStart += 0x1000;

newSlab->m_nextSlab = g_slabList;

g_slabList = newSlab;

Now we can allocate the block of memory inside the slab.

newSlab->Alloc(size, newLoc);

return (void*)newLoc;

}

I have intentionally kept the code here simple meaning there is a lot of room here for optimisation. For example you could maintain multiple slab linked lists allowing you to skip over slabs that are full or find a slab with the correct allocation size more quickly.

I’ve also missed out some asserts and other safety checks. I’ve included those in the full version below.

Freeing memory

To keep things simple we’re only going to free memory inside each slab - once a slab has been allocated it is alive forever! A more fancy version would throw away everything that’s been allocated.

The free function simply asks each slab if it wants to free the block. Again you could be much cleverer and have multiple lists so you can find the slab much more quickly.

void kfree(void* ptr)

{

if (!ptr)

return;

u32 loc = (u32)ptr;

for (Slab* slab = g_slabList; slab; slab = slab->m_nextSlab)

if (slab->Free(loc))

return;

}

Final bits

That’s the core stuff! All we need now is an init function and a main function to test this thing. The init function allocates the first metadata block and sets up the globals.

void kalloc_init(u32 memStart, u32 memSize)

{

g_memStart = memStart;

g_slabList = nullptr;

g_slabMetaData = alloc_slab_meta(g_memStart);

g_memStart += 0x1000;

}

You don’t need your very own operating system to test this! We can point this code at a block of memory, like this:

char g_memory[1024*1024];// 1 MB!

int main(int argc, char** argv)

{

kalloc_init(&g_memory[0], sizeof(g_memory));

}

You can download the whole file here and then compile and run it like this:

gcc kalloc.cpp --std=c++11 -m32 -o kalloc && ./kalloc

This also includes a couple of simple test routines. Note there are almost certainly bugs - please don’t use this in code you care about ;)

Conclusion

So that’s how the slab allocator works which concludes this tutorial!

In a future tutorial series I’m going to talk about setting up virtual memory and interrupts. You might also be interested in the previous tutorial series I wrote on how to write a bootloader!.